February 17, 2021

When Milo was in kindergarten, I read Seth Godin’s Stop Stealing Dreams, which argues that schools are no longer the appropriate way to educate children. The essay haunted me for years, as I sent Milo to public school, to sit in a chair all day and have uninteresting (to him) information pushed on him.

Two months into Milo’s 7th grade, Jen and I decided to pull him out for two years. Reasons included:

The experience was such a surprise that I think it’s worth writing it up for those who are considering it.

Initially we found a few homeschooling books and online classes (such as Outschool) and made a token effort to help him through them. Of course as a 13-year-old boy, all he wanted to do was play video games, and he’d race through whatever worksheets he’d been assigned so he could get back to Minecraft.

This got tiring, so I eventually told him that since his friends get out of school at 3:30pm, before that he can’t play games no matter what, and after that he doesn’t have to do any schoolwork and can play all he wants, just like his friends. In addition, since the books and online classes we’d given him didn’t fill up all his hours before 3:30pm, he could spend the extra time doing anything at all as long as he was learning.

I would walk into his room at 3:29pm and find him counting down the seconds to launching Minecraft. This happened week after week. He’d fill the first half of his day with assigned work, or he’d find some YouTube tutorial that interested him, but he stopped the minute he could.

Then one day I walked in at 4pm and he was still following some online tutorial, I think for how to do something in Photoshop. I quietly walked back out. A week later I found him still doing learning-related work at 5pm. Then a few weeks later at 6pm. Within six months he was aggressively learning seven days per week, every hour of the day. He played a few hours of video games per week.

The learning was entirely self-driven. He’d wake up and think, “Hey, I wonder how they pull green screens for visual effects,” watch five YouTube tutorials on it, shoot some video against a green sheet, and spend the rest of the day pulling green screens in Photoshop and After Effects. The next day he’d get inspired to make a weird gear mechanism, model it in Fusion 360, 3D print it, and iterate until it worked well. The day after that he’d write a video game in Pico-8.

Jen and I found this so great that we backed off on the material we asked him to do. We had read about “unschooling”, especially from David Friedman, and while it’d seemed crazy to us at the time, here we were effectively doing it. The second year, Jen spent an hour or so per day teaching him French (from her high school textbook!), and I spent 30 minute per week teaching him pre-algebra. (Yes, per week, it was an excellent 50-chapter book and each chapter was only a few pages.)

During that time he slowly lost contact with his friends and made fewer attempts to meet them after school. This worried us somewhat, and for various reasons we put him back into public school for freshman year. Despite having spent nearly no time learning math for two years, and zero time learning any other academic subject, he found himself at the top of his grade in math and sailed through the year with straight As. This also surprised us—we had expected him to need remedial work.

So, what happened? Why did it take six months for him to get into the self-learning groove? I now make a distinction between education and learning. With education someone else decides what they’re going to teach you, and they push it onto you. With learning you get interested in a questions and pull the answer from books, people, videos, and other resources, and the information sticks.

I don’t think there’s much overlap between education and learning. Rarely a student will be interested in what the teacher is teaching (by coincidence or because the teacher is good at generating interest), and when that happens, the information sticks. But most of the time the two are unrelated and the student remembers little.

We’re all told that education and learning are the same—if education is happening, then learning is happening. And students go through years of education. No wonder they think that learning is something to be avoided! They’ve rarely actually experienced it. We all figure out that education (and, incorrectly, learning) is a game where the teacher tries to get you to remember something and you try to do as little work as possible while getting acceptable grades.

When Milo started homeschooling, he was still in that mindset. He’d do whatever minimal work he needed to check off his assignment so he could get back to what he knew he’d enjoy: video games. It took months for him to detox and realize the education and learning are mostly unrelated, and that it’s possible (and fun!) to be inspired to learn something.

When Covid caused the schools to close, it took about two weeks to detox again—much faster than the first time.

It’s important to give the student near-complete control over what they’re learning. We told him he could do anything as long as he was learning. (Not “as long as it’s educational” — avoid education!) He could have cheated and said that Minecraft was learning (and in many ways I would have agreed!), but he took it more seriously and pursued interests that weren’t about playing games. (He did end up spending quite a bit of time learning how to program them.)

If you decide to homeschool, the most common question you’ll get from friends is, “What curriculum are you going to follow?” As soon as you use the word “curriculum”, you’ve already lost. You’re doing education, not learning, because the student isn’t pulling information they’re excited about, they’re having your curriculum pushed on them.

When we’ve described this process to friends, some have told us that it would never work for their children. Their children would never adapt to learning. They may be right, but they certainly won’t know until they try. You can’t guess, even knowing your own kid, what will happen when they’re free (and encouraged) to learn. No one does — it’s probably not happened since preschool. I suspect these same parents would never stand for a mostly hands-off approach anyway. They’d probably succumb to picking and enforcing a curriculum, dooming the whole experiment to failure from the start. We already know education doesn’t work, there’s no point in trying it some more!

Freshman year turned out mostly like we expected: No learning happened (except between classes when Milo programmed his TI-84 graphing calculator to make games), and Jen and I felt awful about it. Every week we offered to take him home again, and every week he told us that the social interactions at lunch made it all worthwhile. It was killing us, though, that the years of his life most amenable to learning were the years where the least learning was happening.

School was still remote for Sophomore year because of Covid, and the teachers were hopelessly unable to get any teaching done over Zoom. Six weeks into it he asked to be pulled out. We gave him various choices, and he opted for an online high school. The high school doesn’t ask much of him, and he spends much of his day playing and writing video games.

So, are we “unschooling” him if we’re sending him to an online high school? “Schooling” is forcing the child to go to a school, “homeschooling” is forcing them to be educated at home, but “unschooling” is not forcing them to not be educated. Unschooling means not forcing them at all — giving them the choice. If they want to write video games, they can. If they want to go to an online high school, they can. And if they want to return to their local public high school because their lunch group is fun, they can.

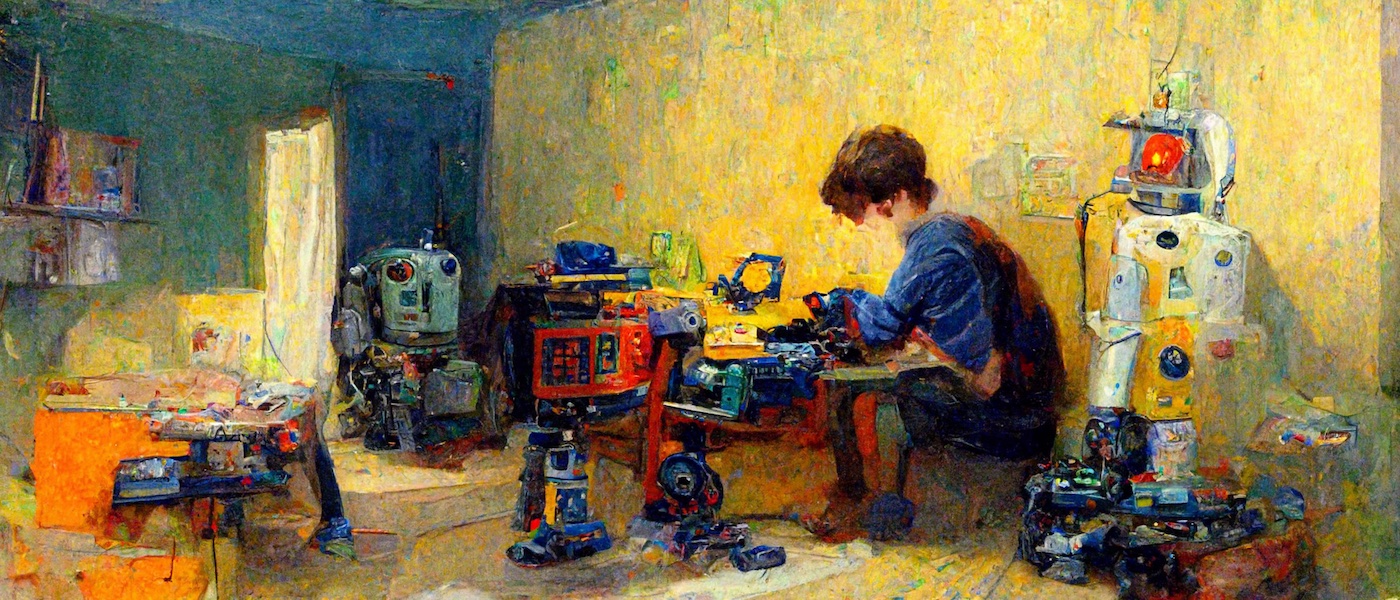

(Cover image credit: Midjourney, “Impressionist painting of a teenager building a robot in their bedroom.”)