Science and Religion

May 15, 2006

I’ve spent the better part of the last two years reading about evolution and, more generally, the philosophy of science. It has changed the way I see faith and beliefs, and in some ways I’m a more solid atheist than ever, and yet I feel a stronger connection to religion. This rambling essay will attempt to explore some of my ideas on this broad subject.

(Note: when I write “scientist” in this essay I’m not referring to the guy in the white lab coat injecting things into mice. I’m talking about a person who believes in the philosophy of science. By this definition I’m a scientist, yet I never touch a pipette.)

Science is a faith

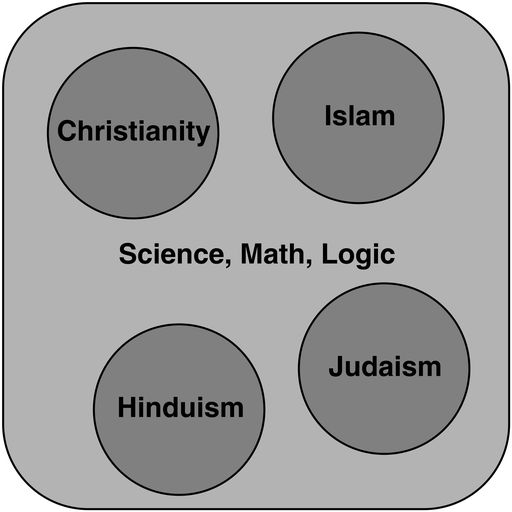

I think it’s common for people (especially scientists) to see the world this way, Venn-diagram-style:

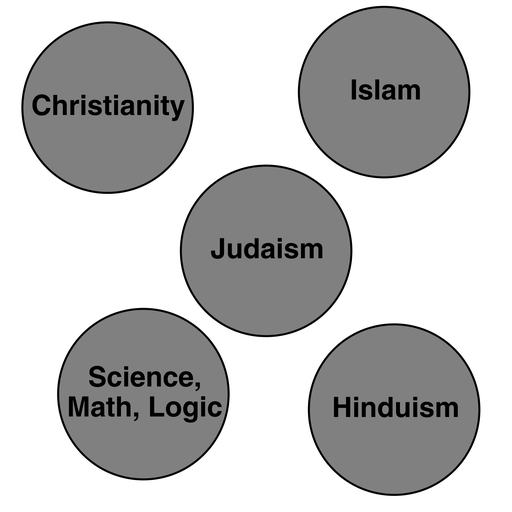

In other words, science and logic and math are basic truths of the universe, and religions are pools of beliefs and faiths within these truths. Instead I think it’s more like this:

Science and logic and math are faiths too, on equal footing with the religions. That first view of the world leads scientists to complain that, for example, religions aren’t internally consistent. But with the second view it’s clear why that is: consistency is a value of science, and therefore doesn’t (necessarily) apply to the other circles.

It follows that science is faith-based. At a high level that applies to things like the scientific method. I have faith that the scientific method is the best way to get closer to the Truth. I have faith that Occam’s Razor’s judgment is more likely to be correct than not. A religious person may not have any of these faiths. For a Christian, reading the Bible is the best way to get closer to the Truth.

On a more basic level, I have faith in math and logic. For example, what’s 2 + 3? Is it 5? How do you know? Well obviously you memorized it from school, but if you had to prove it now, how would you do it? Maybe you could line up 2 sticks and 3 sticks and the definition of “sum” is what you get when you count all the sticks, and you count 5 sticks. So fine, 2 + 3 = 5 today. But what will 2 + 3 be tomorrow? You can’t use the stick method for that, at least not today. I have faith that 2 + 3 will equal 5 tomorrow, and that comes from my faith in math. But a religious person would have to admit that tomorrow 2 + 3 will be whatever God wants it to be. It’ll probably be 5, but if God can do all the miracles in the Bible, certainly he’s capable of showing you 6 sticks when you’ve put down 2 and then 3.

We’d like to believe that, at least, logic and math are provably true, like in the first diagram above. But we can’t do that. The proofs we’d have to use would ultimately reduce to axioms, which are unproven assumptions, and besides the entire concept of a proof is only valid to those who have faith in logic. We must accept that any argument for the truth of math and logic and the philosophy of science would be circular, much like when a Christian says that Christianity is true because the Bible says so.

What implications does this have? At the very least, we (scientists) must admit that we have no objective way to show that we’re right and they’re wrong. We have faith in our values and they have faith in theirs. That doesn’t mean that we have no beliefs. It just means that we have no external validation for those beliefs. This should make us humble. I am sure that I am right, yet I must admit that I do not have a leg up on the other circles.

It also means that practically any debate between the circles is pointless. Scientists inevitably use their own rules when arguing, but these rules don’t apply outside their circle. It’s very common to see this. A scientist will try to point out inconsistencies in the Bible, when the “Christianity” circle does not require consistency. It’s not one of their values. So the attack has no effect. Similarly, the Christian will try to attack Charles Darwin personally, saying that Darwin said on his deathbed that he no longer believed in evolution. I don’t know if that’s true, but it’s irrelevant to the scientist. The evidence in support of evolution is overwhelming, we don’t need Darwin’s personal endorsement.

These two groups use tools that would work on themselves. If someone found a contradiction within science, it would be deadly. If someone could prove that Jesus admitted on the cross that the whole thing was a joke, it would be devastating to Christianity. But these attacks don’t work on the other side.

And it’s more than just attacks, it’s also a root cause of misunderstandings. In the Intelligent Design debate, Christians often point out that scientists don’t agree internally on many points of evolution. But in science, that’s a strength. You never want a single theory, that would leave you with no options, no experiments to run to see which theory is better. Debate and disagreement is an important part of the process. In most religions, however, internal disagreement is a weakness.

There’s another interesting fundamental difference. In science, evidence is critical. A theory with no supporting evidence is very weak. It only exists because other theories are even weaker. But to a religious person, it’s the lack of evidence that’s important. It’s too easy to believe something if you have evidence. Any fool can do that. It takes real faith to believe something when you have no evidence at all. It’s best of all if you keep believing even in the face of contrary evidence! We can have no hope to reconcile these worlds.

Can a scientist believe in God?

It’s often said that science cannot prove God’s existence or disprove it. This is a meaningless statement. That’s not how science works. For one thing, the statement first assumes the existence of God, which is bound to get us into trouble further down the proof. The scientific way to approach the question is to imagine two theories. Theory A says that there is a God, perhaps the Christian God, it doesn’t much matter. Theory B says that there is no God. (Science is supposed to restrict its theories to natural phenomena, but we’ll make an exception here to see where it leads us.)

Firstly, is there any reason to discard either theory outright, based on experimental evidence? No, I don’t think so. Perhaps before 1859 it would have been very difficult to accept Theory B since we didn’t have the most remote idea how life could have come to exist. But now we know that, and we’re left with some questions whose answers are not yet known, but no real deal-breakers.

Then we ask which theory makes more precise predictions. Everything else being equal, we prefer theories that make more precise predictions, since they go out further on a limb and therefore are more at risk of being invalidated. This, when they are not invalidated, makes them stronger. Perhaps here Theory A makes less precise predictions since God could interfere at any time, but that’s not a particularly strong argument in favor of Theory B.

Finally, since these two theories seem more or less equivalent in the most important ways, we can keep the simplest one. This doesn’t mean that the more complicated one is false, it just means that we provisionally choose to accept the simpler one until we find good reasons to do otherwise. In this case the simpler one is Theory B. That’s because Theory A is a superset of it. It includes all of Theory B plus a very complex entity called God.

For example, we don’t know what caused the Big Bang. This is a problem with Theory B. But with Theory A we’re no better off. We can say that God caused the Big Bang (if we even still believe in the Big Bang), but now we’ve just replaced one question with another: what caused (created) God? And “God has always existed” is a completely unsatisfactory answer. In fact we’ve replaced one question with a thousand unanswerable questions. I could ask questions about God all day, like how much he meddles with our day-to-day lives, how long he’s been around, what’s his purpose in creating us, why did he cause the Big Bang, and so on. Theory A is far more complex. In includes a very complex entity and has far more unanswered questions, and doesn’t satisfactorily address any shortcoming of Theory B.

So I think a scientist would have to provisionally believe that there is no God. I say “provisionally” since we don’t have evidence of the inexistence of God, and are unlikely to ever have such evidence, so we must keep our minds open. Perhaps we’ll one day discover something that makes Theory A less complex than Theory B, or maybe Theory B will get discarded altogether. Like maybe God will come down and start talking to us. When that happens, the “science” circle and another circle (the circle whose God turned out to really exist) will merge and physics textbooks will add a chapter on God.

Until then, I think that science’s preferred view of the world must not include a God.

There’s one interesting implication of this. I think that the “science” circle in the above diagram is the only exclusive faith. If you’re a scientist, at least one with intellectual integrity, you cannot believe in the other circles. You’re solidly within the science circle and nowhere else. But the other circles are not necessarily exclusive. Christianity has a decree that “Thou Shalt Have No Other Gods Before Me”, and surely another religion has something similar, so to believe in both would be a contradiction. But neither of these has anything against contradictions!

I’ve heard it said that God sometimes “reveals himself” to individuals in such an obvious way that His existence becomes evident, but only to that person. As a scientist, what am I to make of this? Again the scientific approach would be to make two theories, which we’ll call Theory C (God exists and revealed himself) and Theory D (the person had a hallucination). As an outsider I have no way to distinguish between the two scenarios. I cannot do any test to invalidate either theory. But I do know that people have hallucinations all the time, about a wide variety of things. So Theory D is at least very plausible. Theory C has all the problems of the previous Theory A, namely its complexity. So again I’m forced to provisionally believe Theory D, until I have a better way to distinguish between the two.

But what if this were to happen to me? What if I felt that God had revealed himself to me? It would surely be a very powerful experience, but if I have any intellectual integrity at all, then I would have to admit that I am in no better position to distinguish between Theories C and D than does the external observer. A hallucination seems completely real, by definition. So again I would have to choose the simpler Theory D.

I used the term “intellectual integrity” above, and I want to explain what I mean by that. There are things that we wish were true, and there are things that we think are true. Intellectual integrity is not letting the former contaminate the latter. I don’t believe in an afterlife, but I wish there were an afterlife. My wish (and it’s a very strong wish!) does not affect my thoughts on the matter. Lack of intellectual integrity is, I believe, the heart of the reason why people believe in God. The belief just makes them happier.

The fact that a believer is happier than a skeptic is no more to the point than the fact that a drunken man is happier than a sober one. The happiness of credulity is a cheap and dangerous quality.—George Bernard Shaw

Now we’re faced with an important question. Given the choice between, on one hand, happiness with lack of intellectual integrity, and on the other the opposite, is it really wrong to choose happiness? It’s not quite so polarized; I’m quite happy myself. But there must be a great comfort to believing that God has a plan for you and that, ultimately, you will live happily forever in heaven with your family. Although I choose intellectual integrity myself, I cannot really blame the person who passes it up in favor of the comfort.

So is there any way that science is objectively different than religions? Richard Dawkins, at the end of his otherwise excellent essay Viruses of the Mind, says that science is different (and better) because it favors the virtues of repeatability, consistency, evidential support, and so on. But this is a circular argument, since only science values these things.

Yet I do think there’s a difference. At the heart of it, people believe in God because it makes them feel better. Here “better” is in quotes: if you grew up as a Catholic, perhaps feeling guilty is what satisfies you, in a strange way, and Catholicism gives you plenty to feel guilty about. Or some religions give their followers excuses to be angry and violent. But science does not make me happy. I don’t believe it because it satisfies my wants. In fact it does not satisfy my wants. My want is to believe that bad people will eventually be punished in an afterlife. So that’s one difference between science and religion. Scientists believe in spite of how it makes them feel.

The domain of science

I think it’s okay for science to examine all things, and apply its axioms and theories and methods to all questions of knowledge. That includes metaphysics, religion, and even the question of the existence of a god. If science then provisionally decides to not believe in the existence of a god, based on its “Occam’s Razor” axiom, then that’s fine, and it’s proper for it to do so. (Science won’t do that for all sorts of reasons, but I think it would be okay if it did.) There’s nothing inherent in the low-level methods of science that make them stop working at the physical/metaphysical boundary.

I also think it’s okay for religion to examine all things, and apply its axioms the same way. If some versions of Christianity have the axiom “the Bible is literally true”, then it’s okay for them to believe the earth is 6000 years old, trumping physical evidence. I support that. Religion is not bound to science’s axioms any more than the opposite.

There should not be an artificial barrier where one side is not allowed to examine and judge things from the other side. Each side can use its axioms for whatever it wants, and should. And it should be no surprise that they come to different conclusions since they started out with different assumptions. Neither judgment is more objectively correct than the other, though we each have a preference, and this preference ultimately stems from which axioms we feel more comfortable with.

What we have now is an uneasy truce where science tries to limit itself to physical things and religion to metaphysical things, and they step on each other’s toes sometimes, like when discussing cosmology. I don’t see a good argument for this division of domain. Religion used to have both, and they have been increasingly marginalized, and this is at the heart of a lot of anger in the religious communities. Let them both have both domains. I think that’s a more honest way for things to be.

Atheism

There are lots of different types of atheism and its variants: weak atheism, strong atheism, gnostic atheism, agnostic atheism, weak agnosticism, strong agnosticism, nontheism, ignosticism, antitheism, apatheism, and surely others. People get very specific about their particular beliefs, debating the differences between “I don’t believe a God exists”, “I believe that God does not exist”, “I lack the belief in the existence of God” and so on.

To me these aren’t really differences at all. It comes down to this: when you imagine all of existence, when you think about your mental model of the entire universe and everything that exists, does that model include a God or not? If not, then you’re an atheist. Everything else is just syntactic fine-tuning, probably to avoid making a commitment or seeming to step on religious people’s toes. There’s also a very strong anti-atheism feeling in America, so I can understand people trying to avoid appearing to be an atheist in the strong sense of the word.

People often ask atheists why they don’t just commit suicide immediately. I think that’s a fascinating question, because I want to ask the same question of religious people. As an atheist, my life on earth is all I’ve got. I must make the most of it because when I’m dead, it’s the end of my story. But a religious person gets eternal life in heaven (he hopes), so why suffer down here with the rest of us suckers? It’s no accident that successful religions prohibit suicide. I wonder how many religions went extinct because they didn’t patch that loophole early enough. The People’s Temple of Jonestown and the Heaven’s Gate cult come to mind.

People often wonder why atheists are moral. That’s a much better question. Religious people behave morally because otherwise they’ll be punished by God, either in this life or afterwards. That doesn’t mean they’re moral, it just means they behave morally. It’s hard to know how they would behave in the absence of threats. I behave (mostly) morally because I would feel badly otherwise, but that doesn’t really answer the question. I suspect that the internal morality of both atheists and religious people are based entirely on their upbringing (i.e., their parents). Our religious outlook has little effect on our internal moral compass. But that’s just a guess.

Intelligent Design

I used to think that Intelligent Design was stupid. This is how I saw it: Religions forever have taken credit for what we didn’t understand. They took credit for the sun marching through the sky, for lightning, for life, and so on. As science figured these things out one by one, religion lost ground and became marginalized. The explanation for life was the second-to-last piece in the puzzle. (The creation of the universe is the last piece.) So to me Intelligent Design was doing to evolution what it used to do to the whole world. They would look at the theory, find the parts that we didn’t understand, and claim credit for it. But this is a short-sighted strategy. Eventually these holes will get plugged. In fact ID advocates wrote books a decade ago pointing out holes that have since been plugged, and in a century the remaining holes will be so obscure no one but biologists will even be able to understand them.

Our ignorance is God; what we know is science.—Robert Ingersoll

So that’s why I thought it was stupid: because it’s a losing strategy. But the Dover trial has changed my mind. ID isn’t about claiming credit for the holes in evolution, it’s about literal Biblical Creationism. So ID isn’t stupid, it’s outright fiction.

And speaking of fiction, perhaps this is a good place to show how an atheist sees religion, since it can be hard for a religious person to imagine this. Let’s say that someone walks up to you and says that he’s a Potterist. He believes in the gospel of Harry Potter. All the books of Harry Potter are literally true, and that’s his faith. You would try to explain to him that these are books of fiction, but he would insist that there’s a lot of evidence within these books that they are factually true. For example, they refer to a city called Bristol, which really exists in England.

This person would then try to pass various laws in your state, like a law that forces history teachers in public high schools to teach the history of magic, another that closes down all Christian churches because of their history of burning witches, and another that strips everyone of their civil rights in order to make it easier to find supporters of You-Know-Who. You would be incredulous. What would you do? Would you try to point out little inconsistencies in the books, like maybe in book 3 the stairwell to the dormitories was on the left but in book 6 it’s on the right? The Potterist would reply that stairwells move around regularly in the magical world of Hogwarts. (He’s right, they do.) Would you take him to J. K. Rowling and get her to admit that she made up the stories? The Potterist would reply that Dumbledore used the Imperius Curse to write through Rowling. Do you feel somehow powerless against this person? Do you feel sorry for his delusion, yet are afraid of his desire to control you because of it? That’s how I feel. Now imagine that Potterists make up 75% of your country and they want to change the Constitution.

This is why I don’t debate with Christians (or any other religious group). That would be like debating with a Potterist. To debate with them would give their idea legitemacy, as if there’s even a shred of chance that they’re right. It’s fiction, plain and simple.

The best answer to Intelligent Design advocates is to simply say that if ID is true, then science will eventually figure that out, and there’s no point in forcing schools to prematurely adopt it. Science is a self-correcting system. Those who truly have faith in ID should let the process of science takes its course. On my side, I’m not really concerned about the ID debate, or that ID advocates will win. In 500 years everyone will believe in evolution, the way that everyone now believes that the planets go around the sun. Conservatives eventually die and take their stubbornness with them.

Religion in America

Christianity is particularly strong in America. For example, about 45% of Americans believe that Man was created in the last 10,000 years. Compare this to the second-highest figure in Western countries: 5% in Australia. I’ve often heard this attributed this religiousness to the Puritans. I don’t particularly believe this, though. I can’t imagine that they had this large of an effect on the tides of immigrants. My current theory is that this is a result of the anti-Communism of the 1950s, since Communists were atheists. If that’s the case, then the Soviet Union damaged this country more than they know.

According to an excellent book I read recently, 22% of Americans are certain that Armageddon will happen in the next 50 years, and another 22% think it is very likely that it will happen in the next 50 years. So firstly, 44% of Americans are certifiable wackos. Secondly, 44% of Americans don’t care what happens to the earth after 50 years. This explains our environmental policies, for example. (And our current president is surely in this 44%, probably the first half.)

I suspect, though, that things aren’t nearly as bad as they seem. Surveys show that a large percentage (compared to Europe) of people go to church every week, but the survey-takers say that their numbers are probably vastly overstated because people feel as though they should go to church, so they lie to the survey-takers. Also if you read textbooks from a century ago you can see the progress we’ve made. I read an excerpt from a geology textbook that explained that the earth spun because God wanted to give all Men a chance to see the Sun. (My explanation is that the earth turns because there are more ways to turn than to not turn. Given a random angular momentum, the probability that it’ll be zero is very small.)

After doing research for this section of this essay I relaxed a lot about the sad state of what some people now call Jesusland. I think people are actually getting less religious.

But another thing is clear in America: anti-atheism. As strong as homophobia is, people would still prefer a gay president to an atheist one (by a long shot). This lends support to the theory that America is religious as a reaction to the atheist Communists. I must admit I’m very nervous about publishing this essay, and the possible fallout if it were read by my current or future employer. What an uncomfortable feeling.

Religion in schools

If science and religion are both faiths, then why are we so willing to let the government teach a science class but so reluctant to let it teach a Christianity class? 75% of Americans considers themselves to be “Christian”. And 45% of Americans think that Man was created from scratch in the last 10,000 years (i.e., literal Creationism). This completely contradicts everything we know through science. It contradicts the domain knowledge of hundreds of thousands of scientists and all available evidence. This 45% does not believe in science, apparently. That implies that, at most, 55% of Americans believe in science. 55% is less than 75%. And yet we teach science.

One answer is that there’s actually nothing wrong with teaching religion as long as it’s in a religion class and not a science class. But really you don’t find “Christianity” classes in public schools, but there are plenty of biology classes.

I think the better answer is that most people see “science” not as a belief system but as a practical set of behaviors to come up with some answers. Like you can do stuff in a test tube and maybe learn something about chemicals or diseases. That’s pretty harmless stuff. The scientist is the guy in the white lab coat who’s going to help us beat the Russians, not the guy who uses the scientific method to stop believing in Christianity.

For the most part, in school, we learn science facts (like the periodic table), not science theory (like the scientific method). If science classes spent a lot of time indoctrinating students that all beliefs should be based on the evidence of repeatable randomized double-blind placebo-controlled experiments, you’d have a lot more resistance to science classes in the American public.

The evolution of religion

The great irony is that religions themselves go through an evolutionary process. We judge the success of a religion by the number of its believers, and that number grows if the religion does something to make it grow. Perhaps it has particularly appealing ideas (like a personal God or the Virgin Mary), or it encourages procreation (by banning contraception), or it makes a large effort to spread its ideas (like the Mormons).

At some point in a religion’s life, an individual will modify it, sometimes slightly and sometimes significantly. If the person is able to convert others, and if these modifications result in a relative growth in the number of believers compared to the parent religion, then it will becomes its own species, so to speak, and perhaps even drive the original religion extinct. There are plenty of examples of this, the most obvious being the Reformation, but also the groups within Protestantism, like the Baptists, the Methodists, and so on. Christianity is itself a descendent species of first-century Judaism, after all.

It seems like you can’t read about any religion without immediately learning that early on there were several different versions that fought to become dominant. In Christianity there’s Arian vs. Constantine, in Islam there’s Sunni and Shi’a, in Bhuddism there’s Nikaya, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. (Bhuddism isn’t really a religion, but as a meme it follows the same evolutionary pattern.)

Biological evolution depends on random mutations, and you could argue that these religious changes weren’t random. Except that, like evolution, you only know about the mutations that survived. So they don’t look random, they look thought-out. There were thousands of mutations that for whatever reason didn’t survive. Maybe they didn’t patch the suicide loophole. Maybe the apostles were lazy. There were supposedly a great number of messiahs that were surprisingly Jesus-like. (One example is Mithraism, where Mithra was born of a virgin, his birth was celebrated on December 25th, performed miracles with 12 disciples, held a last supper, resurrected after three days on the spring equinox, and ascended to heaven.) If we could see all the variations that went extinct, in the evolution of both religions and life forms, the process would look a lot less thought-out.

Here’s an interesting but probably trite question. Humans seem excessively attracted to religious ideas, including things like the paranormal. Why is that? The obvious guess is that those in our history who believed in such things had some survival advantage over those who didn’t. Maybe they believed God was on their side, or they weren’t afraid of death, so they fought harder. Or maybe religious people murder non-religious people more often than the other way around.

My guess is that the answer is elsewhere. Perhaps our society and language are so complex that, as infants, we must simply believe what we’re told without questioning it. An infant who questioned every rule of language or manners would never get anywhere. Religious beliefs get swept up along with all these unquestioned rules. That’s not a very satisfying answer. It doesn’t explain why adults who otherwise would be skeptical of unusual claims (say in business) believe supernatural claims so easily.

The purpose of life

Those with a religious bias tend to ask questions like, “What is the purpose of life?” They point out that science can’t answer these questions. I even saw an Intelligent Design advocate argue that evolution can’t answer questions like, “Why was I born male and not female?”

Before we ask these questions, though, we must first ask, “Is there a purpose to life?” Only if the answer is yes do you go on to ask what it is. Asking what it is first implies that there is a purpose, and a purpose assumes the existence of someone who had a purpose in mind, which assumes the existence of God. So the whole question assumes that God exists, and no wonder that science and evolution can’t answer it.

(As an aside, the question, “Do you believe in God?” assumes that God exists and that the question is merely asking whether or not you believe in him.)

To an atheist or one who believes in evolution, there is no external purpose to life. We are alive because we happen to have traits that make us have babies faster and more successfully than organisms that have different traits in our niche of the ecosystem. I am male because the male sperm got there first. To look for deeper reasons to these things is to misunderstand reality.

If there’s any purpose in our lives, it is not discovered but created. It is internal. We decide what we have in mind for our own life and what we hope it achieves. The purpose I’ve created for my life is to be happy and to make the world a better place (by my definition, of course). You can create your own purpose. This is far more meaningful than to endlessly wonder what some unknowable external entity had in mind for us.